In the past couple decades, Maggie Walker has made a name for itself as one of the best college preparatory programs in the country. From there, I would go on to the University of Virginia with approximately thirty of my 174 classmates.

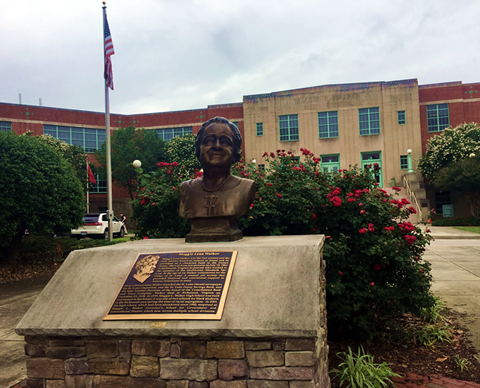

I can say confidently that my classmates and I knew about Maggie Lena Walker, the person. We knew that she was the first female and the first African American to operate a bank in the United States. We knew that she lived in Richmond and some of us even toured her home. A bust was recently constructed on the front lawn of the school to commemorate the woman whose name has become synonymous with academic achievement in Richmond, Virginia.

We celebrate Maggie L. Walker to a degree, but we barely acknowledge the history of the school that occupied our building before it became the Governor’s School.

Maggie L. Walker High School opened in 1938 as an all-black segregated public school. Armstrong High, previously the only black school in Richmond, could not keep up with the growing population. The new facility was well constructed, funded by Roosevelt’s Administration of Public Works. The land for MWHS was provided by Virginia Union University, the HBCU situated right next door. Walker was the first Richmond school to have a black principal and black faculty members. From the start, it was a source of pride to the black community.

As the only two black high schools in Richmond, Armstrong and Walker were natural rivals. Every Thanksgiving weekend, the two schools took to the gridiron in an event called “The Classic” that drew huge crowds. Many members of my father’s family grew up in Richmond and attended these two schools. My grandfather and his mother went to Armstrong, his cousin Fred to Walker. Cousin Fred passed away a few years ago, but the last time I saw him, he reminded me, “You’re going to my school. But I guess it’s a little different now.” I didn’t want to admit that I had never considered this, that there were students and classes and sports teams in the building I called my high school, before it was mine.

Recently, I did a little digging around to learn more about this school that bore the same name as mine, but had few similarities otherwise. I learned that in 1950, interstate 95 was constructed right through the middle of Jackson Ward. Almost three decades later, in 1979, Maggie Walker High School closed. As Jackson Ward declined and whites fled the city, Richmond was left with more high schools than it needed. Walker closed and the impressive facility was left vacant for over twenty years.

In 1990, the Governor’s School—a magnet program for gifted students—began to operate in Thomas Jefferson High School. This Richmond school was previously all white, but began to transition to a predominantly black high school in the 1970s. My father was one of its first black graduates. A few of my teachers at MLWGS were around for what they call “the TJ days.” They remember it as awkward, trying to share space with students from a pseudo-separate high school. They ran on different schedules and occupied different spaces, but it was not a sustainable system. The Governor’s School intended to transition to full occupation of the TJ facility in 1995, but parent protests derailed this plan and the Governor’s School was forced to look elsewhere for a permanent home. In 2002, after a multi-million-dollar renovation, they moved into the former Maggie L. Walker High School building. I was four years old at the time, but this would be my future high school.

When I think about attending MLWGS, I realize our school was hardly a part of the surrounding community. I drove twenty-five minutes into the city daily (twenty if I was running late) and left at the end of the day. Sometimes I would walk to the nearby Kroger after school or get lunch on the campus of Virginia Commonwealth University…but for the most part I did not spend much time in Richmond. My experience was not at all unique. As a magnet school, Maggie Walker attracts students from all over central Virginia, gladly coming from far away for this education, but I cannot claim to have been a part of the Richmond community.

When I was a freshman, former Kansas City Chiefs middle-linebacker and NFL Hall of Fame inductee Willie Lanier came to visit my school—his former high school. Today, MLWGS does not have a football team, but it did when he attended and he was undoubtedly a star player. I did not go to the presentation, but I remember my classmates came back with little foam rubber footballs. We put up a plaque and he took a tour and posed for some photos, and then he left and I can’t help but wonder if the school he saw felt even a little bit familiar.

END NOTES

Duke, Daniel Linden. The school that refused to die: continuity and change at Thomas Jefferson High School. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1995.

RAFProductionsvideo. YouTube. December 10, 2011. Accessed April 25, 2017. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uU2hFGCQyxM.

Richardson, Selden, and Maurice Duke. 2008. Built by Blacks: African American architecture and neighborhoods in Richmond. Charleston, SC: History Press.

“Richmond: A Discover Our Shared Heritage Travel Itinerary.” National Parks Service. Accessed April 25, 2017. https://www.nps.gov/nr/travel/richmond/maggiewalkerhighschool.html.