As a child, many of my fondest memories are connected to water. I have cheeky pictures that my family always seem to pull out of nowhere, that show me smiling in the bathtub with my beloved toy of choice. In school, my friends and I seemed to always find time to catch up on what happened on the playground, around the water fountain after recess. My parents have snapshots of me and my cousins laughing and running from the cold sprays of water from the hose.

These memories I hold, however, were not always the reality for many children, especially those in the American South, who grew up during the era of Jim Crow. The snapshots in the photo records of American history, involving the precious resource of water, all too often reflect uncertainty, terror, and pain.

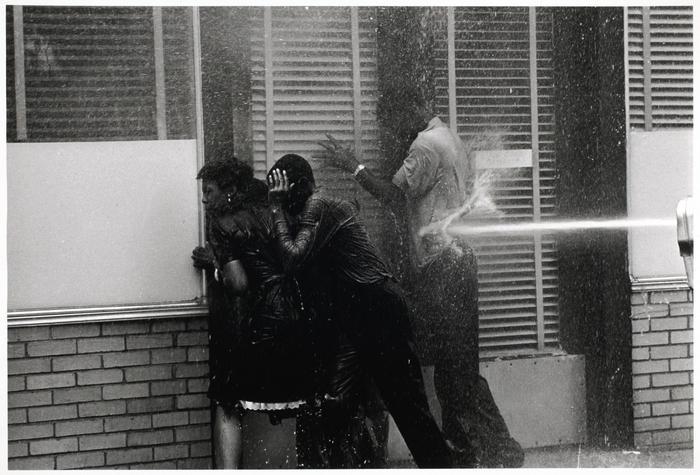

Between the dates of May 2-5, 1963, Black school children of all ages, sizes, gender, and backgrounds assembled at the 16th Street Church to take a stand for civil rights justice. I can only imagine that these brave young people had no idea that something, like water, of which they played in with their brothers and sisters, as well as used to cool, nourish, and care for their bodies would be turned into a weapon by those who opposed their existence. Water, a life giving compound which makes up the majority of our bodies, would for so many of these children leave physiological scars that would follow them long after the May 2nd event.

I was reminded of this, 56 years later, while sitting in a comfortable chair, drinking from my water bottle and absorbing the wisdom of Dr. Tondra L. Loder-Jackson at the University of Virginia’s 2019 Teachers in the Movement Institute. My very presence in this space flowed directly from that moment, when those young people felt the sting of the water spray from the hoses, manned by Birmingham’s local police and fire departments. On that day, the images of their physical and psychological sacrifices, which were reflected on television screens around the world, opened up rivers of opportunities, such as this one, for me.

Prior to May 2, 1963, and for some time after, water would be used as one of many commodities to divide and not unite. Throughout my immersive Teachers in the Movement experience, I thought about the other segregationist tactics used to inflict psychological warfare in the minds of Black children, during the Jim Crow area. I pictured the Black only and White only signs which hung above public water fountains. The Black only fountains often were no more than rust stained sinks pumping warm tap water. Though affixed to the same wall, they were in direct contrast to the modern, White only fountains which had the capability of producing cooling water. For some, water fountain trauma is inconceivable, but for a child thirsting for equal representation and acceptance, as a valuable part of the human race, it most certainly is a reality.

Not all of our time at the Teachers in the Movement Institute was spent inside of a nice comfortable space. As we exited the building, the heat of the Virginia summer brought to mind one of my favorite childhood pastimes involving H20: swimming in the community pool. How can swimming pools cause lasting psychological trauma, one might ask? Imagine the internal, emotional struggle of always being a child looking into the privileged world of others, recreationally enjoying a resource that is supposed to be available to all. Trying to grapple with why you cannot, because of your Black skin, play in a hole in the ground filled with water like the White children. Wondering why the America in which you were born, sees you as more likely to spread communicable disease if you were to enter the water. Why the city in which you were born established laws in which you could be dragged out of a pool and be beaten for just wanting to be a kid. Scarred by the picture of perfectly good water being drained out of the local swimming hole and the surface being scoured with chlorine bleach because you dared to stick your feet in the deep end. I can only imagine.