The Importance of Community

A common theme that I noticed during my time working as a research assistant at the Center for Race and Public Education in the South (CRPES) is that no one can succeed on their own, especially when society is set up for you to fail. Through my work on the Teachers in the Movement project, I observed one thing that is always present when someone is achieving a goal they desire, and that is strong community support. Whether graduating high school, playing sports, attending higher education or garnering a position of influence, strong community support can help people to stay or get back on the right track. The term “community” is not found for everyone in the same place; for some it is a family member and for others it is someone like a teacher or a neighbor.

When considering the need for the community to improve young people’s lives to succeed and flourish, one starts to recognize a massive issue of urban renewal that has and continues to sweep the nation. According to the Merriam Webster Dictionary, the definition of Urban Renewal is, “A construction program to replace or restore substandard buildings in an urban area.”[1] Urban renewal is legal by the U.S. Government and many people consider urban renewal as a way to improve people’s lives. For some that may be true, though for others, such as communities of color or people living in poverty, this could not be further from the truth. By forcing people out of their homes and communities they are taking away a great deal of formal and informal support systems that have been created by communities, many existing for many generations. This renewal process is leading people to have to move away, change schools, not have work and move into usually worse conditioned houses[2]. A great local example of this type of disruption created by urban renewal is when the City of Charlottesville destroyed the thriving black Vinegar Hill Community.

Charlottesville Vinegar Hill Community

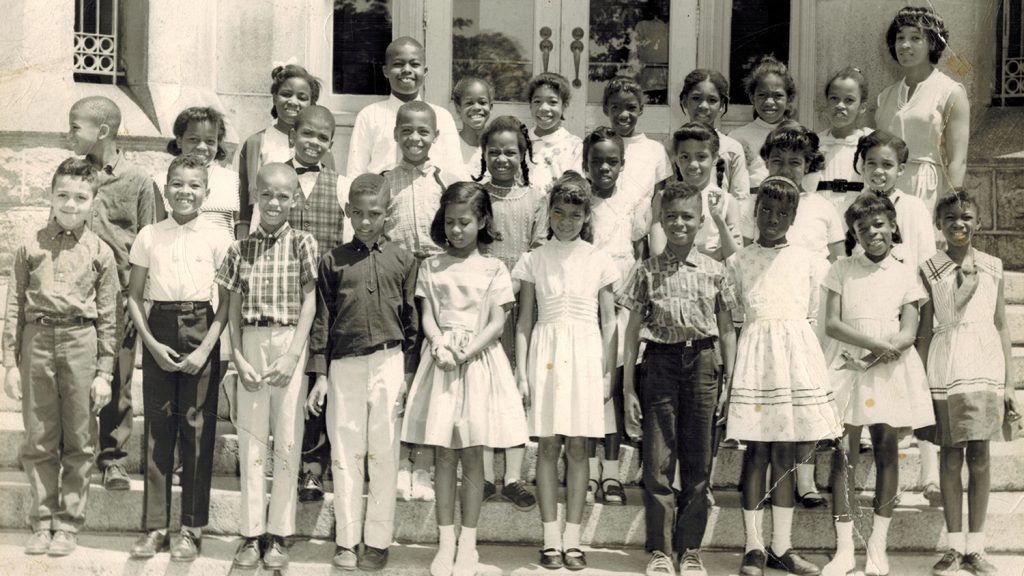

The Vinegar Hill community in 1965 was a thriving black community that consisted of 139 homes, 30 black owned businesses and a church.[3] In the same year the entire community was razed by bulldozers, and the residents were placed into public housing[4]. Many wish this was a one-off incident where people in power made a mistake, but this is a recurring issue that happens in our country still to this day. The razing of Vinegar Hill left the black community in shambles with no economic outlet that still has a generational effect seen today. Many people moved away to seek work elsewhere.[5]

If one was to examine this atrocity in the eyes of what effect this had on youth in that community, it likely would be nothing less than devastating. Children were moved out of their comfort zones; they lost their church, and many had to relocate into a new school. Charlottesville’s urban renewal was supposed to push the city in a more positive direction, however, it made it increasingly more difficult for a whole generation to succeed. This handicap to succeed for this generation is created from the loss of social and economic backing that was generated from the Vinegar Hill Community

Oral Histories in Central Virginia

Collecting oral histories from adults and youth who have experienced urban renewal is an important way to understand more about community. In interviews conducted by UVA’s Teachers in the Movement Project, I noticed the need for community when a child is growing up. The UVA Teachers in the Movement Project examines oral history interviews of educators and administrators during the civil rights movement at all levels of schooling to figure out the role they played in the movement. During my own time in the project, I got to participate in interviews with these educators and learn their stories. One interview that demonstrates this is with Earl Woods, who talked about his experience down the road in Waynesboro, Virginia, a small city outside of Charlottesville. He talked about how the kids in his community were raised collectively by all of the parents and how he could not wait to be a part of the Rosenwald school community. Another great example is Lynn Boyd, whose positive community in Kinston, North Carolina remained intact during her upbringing which allowed her to grow up and flourish as a person; as a result, she has spent her adult life helping youth in Charlottesville by teaching at Burley Middle School for 42 years. Mrs. Boyd is a great example of how a good community can keep improving generation after generation, and how if communities are decimated and taken from people that built them, there will be generational decline for many families for many years to come[6].

What might be the biggest travesty of all, when urban renewal pushes people out of their homes and communities, is that people ignore the past and devalue the residents of the community. I think Charlottesville and other cities need to make a change by working to stop these types of projects and stop viewing the historical monuments that exist in what were once great communities, in which people resided and people lived with family and friends, as positive community growth. The least one can do when they are walking through areas that have been gentrified is take a moment and be a student, learn the history and take a dive into the past. Then from there, share what you learned with someone else! Through educating about the facts of what has happened in the past to people, they are taking part in the practice of oral history, which should have the ultimate effect on impacting modern day society.

___________________________________________________________________________________________

[1] Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Urban Renewal. Merriam-Webster. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/urban%20renewal\.

[2] Smith, L. (2017, September 20). In 1965, the city of Charlottesville demolished a thriving black neighborhood. Medium. https://timeline.com/charlottesville-vinegar-hill-demolished-ba27b6ea69e1.

[3] Smith, L. (2017, September 20). In 1965, the city of Charlottesville demolished a thriving black neighborhood. Medium. https://timeline.com/charlottesville-vinegar-hill-demolished-ba27b6ea69e1.

[4] Smith, L. (2017, September 20). In 1965, the city of Charlottesville demolished a thriving black neighborhood. Medium. https://timeline.com/charlottesville-vinegar-hill-demolished-ba27b6ea69e1.

[5] Smith, L. (2017, September 20). In 1965, the city of Charlottesville demolished a thriving black neighborhood. Medium. https://timeline.com/charlottesville-vinegar-hill-demolished-ba27b6ea69e1.

[6] CRPES Teachers in the Movement Project Database