I attended the Teachers in the Movement Institute at the University of Virginia in Summer 2019 to learn more about ways to connect historical content to both the community and the lived experiences of students. I also hoped to learn about history with meaning and relevance to the issues of our time. Often, classrooms can feel disconnected from current issues in our communities. As a result, students do not always find purpose or applicability of content to their daily lives.

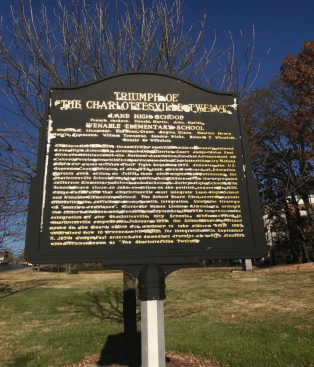

The national attention on Charlottesville since August 11th and 12th, 2017 has forced many in the community to begin reckoning with the past – and part of this reckoning is grappling with our local history and how we remember the past. Young people and students are also aware of this spotlight on Charlottesville and are now asking difficult questions and seeking historical knowledge and content relevant to the issues of race, identity, memory, and equity. Furthermore, in our school systems, there seems to be an institutional willingness to acknowledge that the fight for equity in education continues today and did not end with the Charlottesville Twelve or the Albemarle 26 desegregating local schools after massive resistance.

It is not possible to understand (or teach) the aforementioned topics without examining and unpacking peoples’ experiences within their communities. The history of our community has shaped both the state of local schools today, which also includes issues facing students and the community today. This history has contributed to the building of the collective memory in our community. Not only do we need to hear these stories and preserve these histories; we must give voice to acknowledge the agency and humanity of people who lived through these experiences.

Witnessing Dr. Alridge’s interview in the Rotunda with civil rights era Charlottesville/Albemarle educators during the TIM Institute sparked an idea for me and my students. While I shared little in common with these educators on a personal level, as a teacher I felt connected to them and gained a sense of optimism and appreciation for teaching through their testimonies. And I admired their resolve and perseverance through challenges they faced as teachers during the civil rights era. Their stories of teaching during very difficult times in our country’s history helped me better understand my job as a teacher and the history of the local context that I am teaching in. The educators challenged me to think about whether or not there is a way that my students could also engage in oral history by conducting their own interviews with former teachers and making connections to where we are today.

By asking my students to conduct oral histories with former local students, I hope to 1) forge connections across generations within the community, 2) propose a “critical history” constructed by students through oral history interviews that counters the master narratives about the integration of public schools, 3) chronicle the experiences, challenges, and triumphs of people whose stories may have not been told, and 4) remind young people that history happened here and continues to happen every single day.

Through a Students of Desegregation Oral History Project, students would be tasked with conducting oral histories themselves by interviewing former students who attended school in the community from 1963-2017. Students will ask former students to reflect on their experiences at school and in the community. Not only is this a wonderful opportunity to assign students authentic inquirydriven work of historians that may result in a product worthy of an extended audience, but assignment also encourages students to engage in conversations about the past and collect important stories that would otherwise be lost.

After working to teach students the historical context of the period, high schoolers or middle schoolers could formulate interview questions and record their own oral history interviews in order to learn about the personal experiences of local relatives, business owners, school teachers, administrators, people from their religious communities, coaches, etc. who have experienced school in Charlottesville in the years following desegregation.

This process will go further to remind young people that history happened here and continues to happen every single day. That, in itself, can provide a sense of purpose and meaning to our lives. Furthermore, acknowledging the struggle, efforts, and sacrifices of the previous generation can help provide youth with a sense of duty in our own.

Students are the ones who live day-to-day within our schools, which is why it is so important to recognize the weight of experiences and memory related to our local history. In thinking about the past, it is important for young people to recognize that history is made by individuals and community members rather than only the distant heroes who populate the master narrative.

Teachers should design curricula that encourage their students to authentically engage with important topics relevant to their daily lives and inspire students to connect what they learn and experience in school to their community and the generations of people that came before them. These connections are critical to building cohesive communities and have the potential to empower young people to view themselves as agents of change because of shared knowledge, experiences, needs, and empathy across generations.